Welcome to the 12th edition of Gradient Ascent. I’m Albert Azout, a prior entrepreneur and Founder/Managing Partner at Level Ventures. On a regular basis I encounter interesting scientific research, founders tackling important and difficult problems, and technologies that wow me. I am curious and passionate about machine learning, advanced computing, distributed systems, dev/data/ml-ops, deep tech, and life sciences. In this newsletter, I aim to share what I see, what it means, and why it’s important. I hope you enjoy my ramblings!

Is there an emerging VC fund manager or founder I should meet?

Send me a email

Want to connect?

Find me on LinkedIn

“The empires of the future are the empires of the mind.”

—Winston Churchill

Hi everyone! It has been a while… I have been working on a new business—an AI-powered investment manager focused on venture capital—which has been keeping me busy 🤓.

While I typically write about AI, these days I have also been thinking deeply about investing/capital markets and would like to share a few ideas that I have encountered as well as some examples from venture capital. Here goes…

COMPLEX ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS

Empirically, capital markets exhibit interesting characteristic properties, including leptokurtic return distributions, volatility clustering, boom-and-bust cycles, sudden percolation, which result from the way investors form and execute belief/expectation models. In the neoclassic view, markets are described in terms of their equilibrium states (i.e. supply/demand equilibrium, game theoretic decision making, economic expected utility). In reality, however, markets are far from equilibrium—they are in a constant state of non-equilibrium—they are living, breathing, constantly evolving, and unfathomably complex systems.

In markets, investors are not static participants, they continuously adapt their beliefs and expectations in an environment created by other investors’ beliefs and expectations. Since these expectational models condition an investor’s own thinking, there is an inevitable feedback loop. One can imagine a market as an ecosystem of investor models. This ecosystem evolves via economic selection (see evolutionary game theory)—investor models live or die—forming a complex adaptive system. Complex adaptive systems are both self-organizing (decentralized order/structure formation) and emergent (explaining the emergent phenomena that we see empirically).

Since forecasting complex adaptive systems is an ill-defined problem, investors can never be “rational” as implied by neoclassicism. Rather, they reason and build models inductively—perhaps with bounded rationality—often using heuristics and other reductive biases to make allocation decisions (this has parallels to transfer or meta learning in deep learning, and whether or not generalization to novel environments is possible with pure statistical learning). In some situations, investors completely forego their own beliefs and models and fully mimic the behaviors of other investors (#FOMO). In other situations, they may employ fully speculative behavior, using as input only the price signal, and hoping for a greater fool.

To provide a concrete example of the above dynamics, here is how they play out in in Venture Capital:

VC’s formulate investment theses (active) or extract patterns from deal flow (passive), generating expectational models and strategies.

VC’s expectation models and strategies are not independent but coupled. This coupling results in consensus behaviors, “party rounds”, “hot” thematic investment areas, etc.

Bad investment strategies die. Successful strategies live. A self-organizing network structure emerges— the co-investor network. This emerging network structure is self-reinforcing—for some period of time, successful investors cluster together creating further successful strategies and investment activities.

At points in time, new technologies or novel combinations of technologies “shock” the system, sometimes generating large-scale phase transitions in strategies and network structures. Technologies breed more technologies as innovative technologies become sub-assemblies for other assembled technologies. Investors are forced to adapt their strategies or die out (i.e. crypto is a great example of such a phase transition).

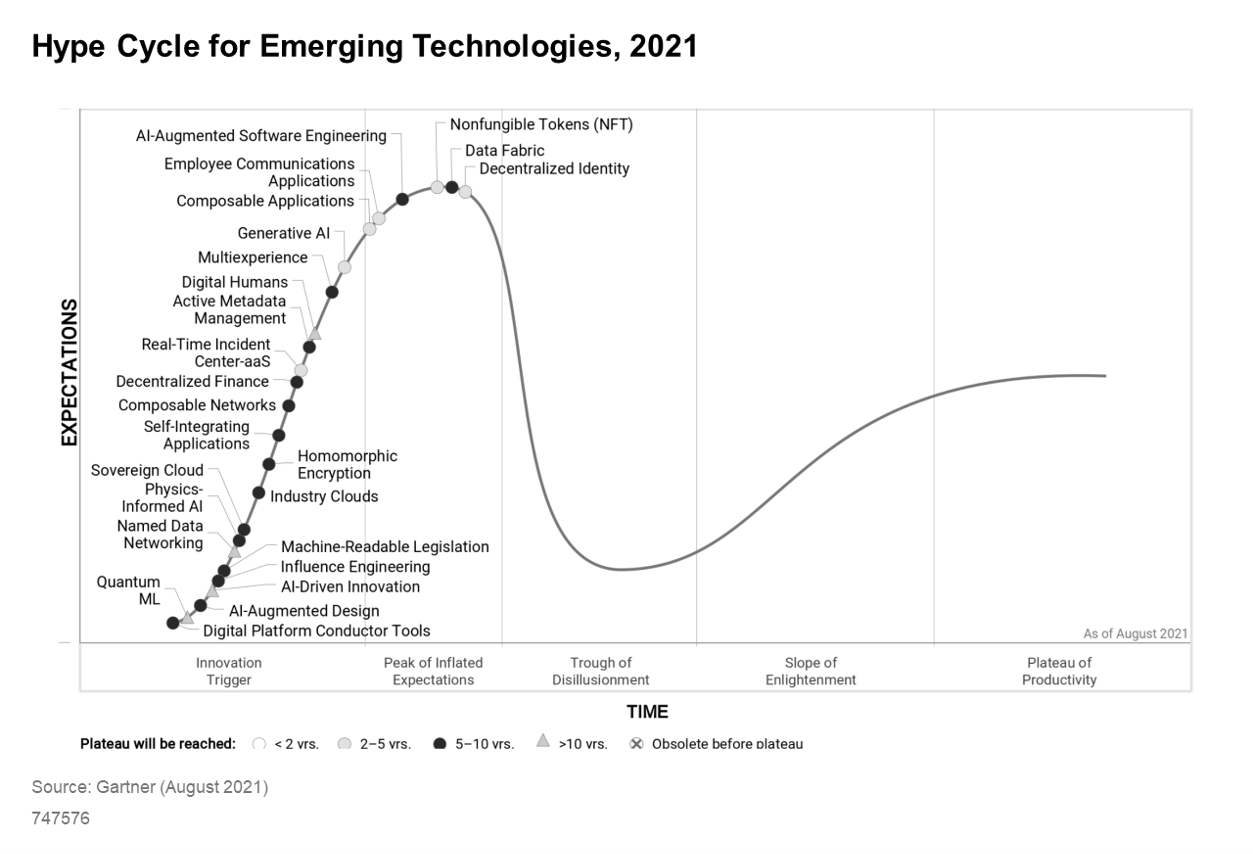

As a result of all this, characteristic properties emerge in VC: (a) power law distributed returns, (b) high dispersion of performance across fund managers, (c) generally low fund manager persistence, and (d) hype cycles (see this post).

I will also mention that, unlike some argue, VC is not “solved” merely by portfolio construction and wishing for outliers. The sequence/path and pacing of investing matters. Borrowing from ergodicity economics, ensemble expectations do not always equal time expectations. In early-stage VC investing, there is a very real risk of ruin.

FEEDBACK LOOPS

Complexity studies the propagation of change through interconnected behavior. Since, in complex systems, agents develop beliefs and models which interact with and are changed by other agent’s beliefs and models, there is an endogenous feedback loop. Feedback loops are a core primitive in complexity theory and complexity economics, and thus in capital markets. When unbalanced, either positively or negatively, feedback loops generate large-scale propagation events, or cascades.

Much like power laws describe return distributions in markets, it has also been shown that cascade sizes (the portion of a network or population “infected” by a given cascade) also follow a power law (also see percolation theory). As an example, see below the log-log plot of cascade sizes in the Twitter network (source).

Outlier cascades (bottom right portion of the chart above) are very rare, but incredibly impactful. In capital markets these outliers represent situations in which investors are fully synchronized (i.e. lack diversity), resulting in what we know as boom-or-bust cycles. In venture capital, this is expressed ostensibly in hype cycles (see below).

REFLEXIVITY

To make things even more interesting, another type of feedback loop exists—the feedback between expectations and an underlying trend. George Soros calls this reflexivity. According to his theory, investors are fallible and operate in a subjective reality, with both a cognitive and a participatory function. The participatory function, as we mentioned above, alters the same reality that investors are trying to understand. As such, there is a feedback loop between the investors and the environment. However, there is also a feedback loop between the asset price (i.e. stocks) and the underlying metric being tracked (i.e. earnings per share, which can be inflated with stock-based acquisitions).

In venture capital, a good example is the multiplication of companies. A large influx of capital into high-growth startups multiplies the number of startups. Startups selling technology often sell to other startups and other tech companies, reinforcing the underlying revenue growth trends, creating more investing activity. This trend reverses in a down-cycle as startups go out of business and tech companies cut costs. Of course there are examples abound.

TAKEAWAYS

In my opinion, here are a few takeaways:

The future is impossible to forecast. As complex adaptive systems are impossible to forecast, one should rather ask what expectational models are dominant and whether you agree with those models.

Embrace uncertainty and the “shock” from technology innovation. Uncertainty is persistent and the economy endogenously generates new technologies, which create further uncertainty. Being overly thesis driven or specialized may be a bad thing over long periods of time.

Be careful about relying on ensemble expectations. Be wary of basing decisions on expected outcomes across “copies of yourself”. One should look at time expectations—what if the bet was repeated over long periods of time, how would my wealth evolve. Are there uncle points? As Howard Marks writes: “there are old investors, and there are bold investors, but there are no old bold investors.”

Always ask: where are the feedback loops? In complex systems, feedback loops always exist. Some negatively reinforce and others positively reinforce. They are hard to see but it seems prudent to ponder what feedback loop we may be stuck in. Although, by definition that question creates a feedback loop 🤪.

Do your own work. Investing (and life) is complex and uncertain. The easiest shortcut is to mimic others or develop overly coherent models of the world. Easiest is likely not to be optimal. Ideally, you should do your own work and invest in what you understand well. As Peter Theil writes: “the most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself”.

NON-SEQUITERS

A great book on investing…

A great book on complexity economics…